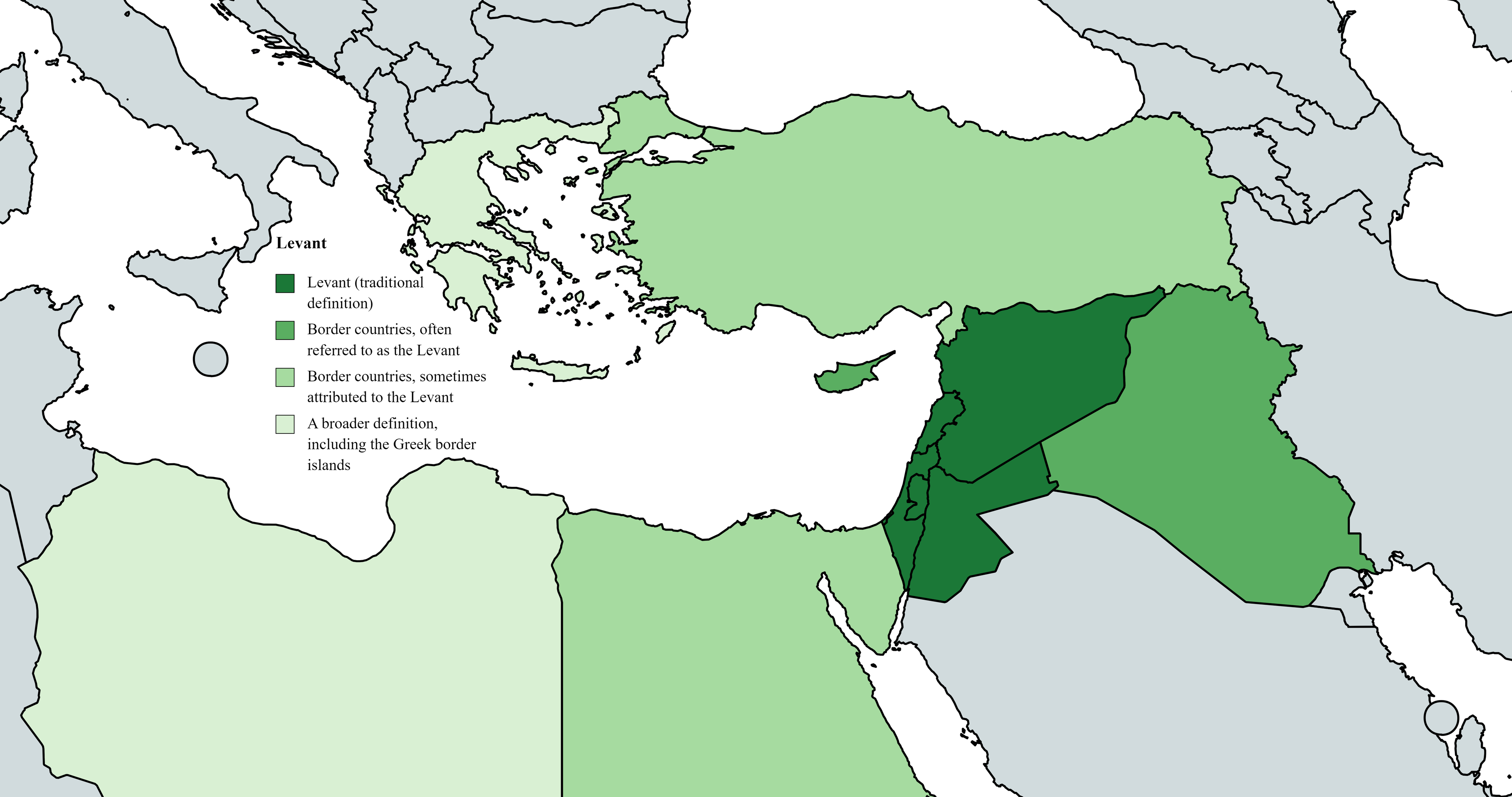

The Levant

The history of winemaking in the Levant—encompassing modern Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Jordan—is arguably the longest continuous viticultural tradition on Earth, dating back to the Neolithic and Bronze Ages (4000–3000 BCE). The Phoenicians, based in what is now Lebanon, were pivotal in this history. As great ancient mariners and merchants from coastal cities like Tyre and Byblos, they didn't just make wine, but exported it across the Mediterranean, spreading the culture of the vine to Greece, Italy, and beyond. This Phoenician-Canaanite wine, often transported in distinctive amphorae (like the Canaanite Jar), was a prized commodity, with the fertile Bekaa Valley in Lebanon having one of the most celebrated and persistent winemaking traditions, evidenced by the massive Roman Temple of Bacchus in Baalbek.

During the Roman and especially the Byzantine periods (4th-7th centuries CE), the winemaking industry of Palestine (particularly the Gaza and Ashkelon regions) and the wider southern Levant boomed into an industrial-scale export powerhouse. The highly sought-after sweet "Gaza Wine" (Vinum Gazetum or Vinum Ashkalonium) was shipped throughout the Mediterranean in characteristic, slender ceramic "Gaza Jars" (LRA 4 amphorae), with archaeological evidence of these containers being found as far as Britain. Large winepresses and run-off agriculture systems in the Negev, Jordan, and the coastal plains attest to this vast production, often supported by growing monastic communities who needed wine for liturgy.

While the rise of Islam in the 7th century led to a commercial decline, winemaking never fully ceased in the region. Production was maintained for Christian and Jewish communities, often in monasteries like Cremisan near Bethlehem in Palestine or Latroun, and within individual families. In Syria, winemaking historically centered around regions like the coastal Mount Bargylus, near Latakia, and the Hauran in the south. Jordan also boasts ancient wine presses and biblical mentions of its vineyards. The French influence in the 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly in Lebanon (e.g., Château Ksara founded by Jesuit monks), helped modernize techniques and re-establish large-scale commercial production, blending ancient indigenous grapes (like Obaideh and Merwah) with classic French varietals. Today, winemakers across the Levant are reviving this ancient craft, celebrating the resilience of their vines and their deep historical connection to the world's most ancient wine terroir.